A Year in Books: 2025

When keeping track of what I read in a given year, I do so via analogue means – a book journal and a pen – and this all started because, once, my grandmother gave me a historical novel that she had found in the attic of my great-grandmother’s house and which I had read, in stints, when hanging out with my grandparents after school. The book eventually disappeared and I spent years searching for it online, going by one of the protagonist’s names and a vague notion of what happened in the story. At long last I did end up finding the title, but I spent the whole arduous search infuriated with myself, because if I’d only written it down, all this work would be totally unnecessary (incidentally, the book was Dinah Lampitt’s To Sleep No More, which did eventually turn back up and is now sitting, happily, on my shelf. I haven’t read it since and these days have only a vague notion of what it was about). So after that, I decided to keep track, both so that I wouldn’t forget the titles and also so that I could flex on people. The latter sadly has not worked, because when I try to tell people that the number of books I read this year was in the double-digits, I’m usually only greeted with a withering look.

I have mentioned previously that I usually read about forty books a year. Alas – this year was different, and I did not quite manage it. As of writing, I have read exactly thirty-one. Not all of them were 2025 releases. I tend to read the things I want when I want to, with little notice given to their publication dates; however, I have had a look back through my diary and it seems like I read more books from the 20s than in previous years. I’m not necessarily sure what that means. Maybe I’ve decided to start living for the present rather than ruminating on a long-gone past? But then again, that seems an excessively over-the-top analysis of something that is actually quite mundane.

So, without further ado - *deep breath* -

January

Strong start. I began the year with a grotesque horror novel, Maeve Fly by C.J. Leede. I read it because it was something I had wanted to read for a while, having seen it on a number of MOST DISTURBING AND FUCKED-UP BOOKS OF ALL TIME lists. Also, it was bought for me for Christmas, so it felt like an obligation.

Maeve works as the Ice Princess at the Theme Park. No brands or companies are explicitly mentioned but it’s obvious who the Ice Princess is supposed to be, and which major entertainment company owns the Theme Park. She gets through the day by snorting coke with her friend Kate. Maeve is the granddaughter of a Golden Age of Hollywood film star. She’s also a serial killer.

Leede is a good writer with equally good technical skill, who weaves an entertaining story whilst also managing to make you feel a bit sick. And she’s certainly imaginative. There’s a point where another character is tortured by means of a tube and a mouse in a place where a mouse emphatically should not be. Bonus points for sickly hideousness, I guess.

Last year I read Moshfegh’s Eileen; the titular Maeve does remind me a bit of her, if a bit more bloodthirsty. What can I say? I like novels with female protagonists who run the gamut from weird losers to sadistic serial killers. Mind you, this one was a bit schlocky at points, which did break the immersion a bit; so if you’re wanting something that will keep you in thrall to its horror the whole way through, this one might not meet specifications. Enjoyed it, though. 6/10.

February

Huge tonal shift now with the second book of the year, Michele Mari’s Verdigris, a work in translation published by & Other Stories. This was something I read for my book club; although I do like & Other Stories, I’m not sure if I’d have picked this one up in a shop if I’d seen it. I bought this one, though that’s just because I couldn’t get hold of it via the library.

The narrator, Michelino, is a thirteen-year-old who spends summers with his grandparents at their estate in northern Italy, squishing slugs and generally being a weird teenage boy. He ends up getting to know the groundskeeper, Felice, an eccentric old man who speaks cryptically and with a strong accent. He is also losing his memory. Michelino takes it upon himself to aid Felice by coming up with a complex series of mnemonics he can use to prolong his memory, but in doing so, Felice ends up sharing secrets. Secrets including the fact that there are Nazi skeletons in the attic.

The thing I remember most about this one was how impressed I was with the language. As mentioned, Verdigris is a work in translation, originally published in Italian in 2007 and expertly transformed into English by Brian Robert Moore in 2024. I’ve always admired people who can speak multiple languages with fluency, and particularly those who can translate literature; things like idioms and poetic turns of phrase do not always translate easily, or well. But Moore has done it brilliantly here. The mnemonics that Michelino and Felice employ have all been carefully crafted to express meaning in English, as an extrapolation from their original Italian. There is a lengthy translator’s note at the back of my copy, explaining why certain decisions were made and how Moore came to them; he writes that “[Moore] wanted this translation to live as a book in English, and remain[…] a unique celebration of language”.

Verdigris is one of those books that I think I will need to read again to fully appreciate it, as I’m sure there’s plenty I missed first time around. The plot is secondary. The language is the most important aspect of this novel. I am glad to have read it. 8/10.

We’re cooking with gas now. The next novel I read in February was Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend, which I have already discussed at length (see the entry on this page dated 30th July), and so I won’t repeat myself here, but I was glued to this one. It is part of a series, and I plan to read the next one, at least, in 2026. My Brilliant Friend deserves all the accolades it gets. 9/10.

March

In March I read Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, which is one of those books that you know you ought to have read and, if you haven’t, you feel obsessively guilty about not having done so, and in constant doubt about your literary cred. So I read it, because I found it at the library whilst looking for something else and decided to give it a try.

The Bell Jar is the only novel that Plath wrote. I am familiar with her poetry inasmuch as I can be, as somebody who does not like poetry overmuch; I can quote the first stanza and a half of Daddy just because I wanted to learn it, and I know that Plath was married to Ted Hughes, was exceedingly miserable, and killed herself by sticking her head in the oven. Reading The Bell Jar made me feel even more sorry for her, because it is less a novel and more a gruesome account of just how unwell she actually was. I want to believe that if Sylvia Plath was alive today, she’d be treated with more grace and sympathy than she ever was in her life – but somehow I don’t think that would be the case at all. I’m really not sure how much we’ve learnt since the days of ECT and insulin shock therapy.

Because the novel is essentially autobiographical, it is difficult to review fairly. You would judge a work of fiction by a number of metrics; but this is not really fiction; ergo, how do you judge it? With a number, I guess. 7/10.

Later on in March, when the sun came out a bit and I could sit outside with my sunglasses on, I read This is How You Remember It by Catherine Prasifka. This one follows You, a You who is female, Irish, and about ten when the story starts. You have a computer, are gifted it by a friend of your dad’s. You play on Neopets and watch YouTube and live a life entirely online. A life that is gradually bogged down by online nastiness, a life that is marked and scarred by incredible cruelty. A life that is not entirely unfamiliar to anybody my approximate age, who got online during the dying breaths of the World Wide Web’s Wild West.

I wrote a piece inspired by this one – more than anything I liked the sense of nostalgia emanating from it, which when you think about it is kind of fucked up – and I had the sense that I could not stop reading. What happens to the nameless, second-person protagonist is not unlike a slowly-unfolding car crash, where you can immediately foresee grievous injury but cannot look away. The moral is that the Internet is a corrupting influence, an all-rotting tar pit that destroys all it touches. The point is hammered home and by God is it hammered – at points, it is very heavy-handed, which makes it difficult to enjoy. But this is something that can be looked past. If nothing else, it deserves points for the interesting manner in which it is written – second-person is hard to do, and I think Prasifka deserves points for that. 7/10.

Next I read Sarah Hall’s seventh novel, Burntcoat, which was published in 2021 and presumably written the year prior, because it follows two people living within the midst of some sort of nasty pandemic, one that is airborne and spreads easily between people. Taken as part of the uneasy oeuvre of Covid literature, this one is easier to stomach as Burntcoat’s virus is emphatically not Covid.

But taken, outside of the pandemic context, as a novel – well. It is difficult for me to actually share my thoughts about this one in a succinct manner, but I will try – Burntcoat is one of the best books I have ever read in my life, and is certainly the best one I read in 2025. It is short, but the glory and wonder and heat and agony of love pulses through every page. The narrator Edith is a sculptor who, just before the world crumbles, embarks on a deep and passionate love affair with an immigrant chef named Halit. They exist only for each other, deep in love and deep in thrall. And then the virus breaks out. There are fights at food banks, curfews are introduced, the army are called in. And then Halit gets sick – and then Halit dies, and what follows is Edith’s attempt to make sense of this new world where law, order, and love have all dried up.

Seriously, just read it. Burntcoat is a work of beautiful genius. 10/10.

A bit of a departure now. Every now and then I do read a children’s book; sometimes for nostalgic reasons, and sometimes because I do like to keep abreast of children’s publishing trends. The next one I read in April was Suzanne Collins’ Sunrise on the Reaping, which I breezed through despite its relatively long length. The reason I read it is because I read the original Hunger Games books when they came out and went absolutely feral for them. I also watched some of the films, though – being a pretentious arsehole even then – declared that they were “not as good as the books” and as a result did not even watch past the second one. (There was no reason for this beyond simply to be irritating).

Sunrise on the Reaping is a prequel and follows Haymitch, a character who I really liked in the original trilogy. For those unaware of The Hunger Games, a quick overview – the modern-day USA is split into twelve (actually, thirteen) districts and each district has to send two children to go off to the glorious shining Capitol to fight to the death on live television, except one year where they had to send four kids each. This was Haymitch’s year. This book chronicles his life, and how he won. For a kids’ book (well, young adult) it’s quite violent, more so than I remember the original trilogy being. This might be down to the fact that I simply do not remember them well enough, or perhaps because modern young adult fiction is increasingly marketed to adults, and are therefore more explicit in their depiction of language, violence, sex, and so on.

I liked dipping my toes back into the world of Panem, though I’m not sure if I would read it again. But if Suzanne Collins were to come out with another Hunger Games book then I probably would read it, so I’m not sure what that says about me. 6/10.

April

April was clearly a busy month for me as I only read two books (I’m pretty sure I began to set up Crushed Marigolds in April, which would explain it). The first I read was a non-fiction title, Jia Tolentino’s 2019 book of essays, Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion.

Tolentino writes for The New Yorker and I like her style. She is funny and self-aware and has a good handle on the topics she discusses, and I had heard very positive things about Trick Mirror and was delighted to find it at the library. Some of the essays stick out more than others in my mind – the first one, a discussion about Internet culture over the years and how its most recent iteration has made narcissists of us all, was particularly good – but what I also enjoyed was the general Tolentino flavour that she imbues every word with.

I realise that her style isn’t for everyone. I know that Lauren Oyler was particularly critical and suggested that Tolentino wrote too much of herself into the essays, which made it hard to actually evaluate the ideas she was trying to discuss. On a more personal note, I also find non-fiction a bit harder to rate than fiction, since I don’t read it as often and it is judged, generally, on different merits. However, many of the concepts that Tolentino writes about (Internet culture, reality TV, the hyperfixation on weddings and marriage) are a bit niche and a bit recent to have been discussed at length. I found Trick Mirror gave a good overview, and I had a pleasant experience reading it anyway. 8/10.

The next book I read was short and topical. Everyone in London was carrying around a copy of Vincenzo Latronico’s Perfection (translated by Sophie Hughes) this year, along with (but not inside of – no no, the Klein blue Fitzcarraldo cover had to be visible) their Daunt Books tote. Sophie and Tom are a couple living in Berlin (but they are not actually from Berlin; they’re not even German) who both work very hard (in their bullshit email jobs – sorry, digital nomad roles) and are in pursuit, as the title suggests, of perfection. The way the light spills through the windows of their perfect little flat is perfect. The work that they put in at their jobs is perfect. Everything is perfect except nothing is, because the two have no connections – not to the other Berliners they come across, nor to the city itself, and not even, really, with each other. They chase and chase this perfection and never ever attain it, because how can you? Your life could be perfect by your own judgement, but it will never be perfect to someone else.

That was my takeaway, anyhow. The whole is written without the use of dialogue, which I found impressive. I read that Latronico apparently thinks that the English translation is better than his original Italian, which – being a filthy monolingual – I could not possibly judge. Hughes, however, clearly did a good job of the translation if this is the prevailing view.

Perfection made me, somehow, nostalgic for living in a Berlin flat and having a job where all I do is answer emails, which is weird because I have literally never experienced that. So Latronico certainly gets points for that – escapism at its finest. 8/10.

May

And then it was May. Contrary to my reading habits in April, this was a busy month. I read five books in total, my busiest month, though two of them were quite short and one was a children’s book (this is the last children’s book of the list, I promise).

First up I read Evie Wyld’s The Bass Rock, which was a book club pick and not the sort of thing I’d normally choose for myself. It tells three stories which are linked, but on the face of it, only tenuously so. The narrator of the one set in the present day is some sort of step-relative of the protagonist of the postwar one, and the third – following a priest and a boy rescuing a girl accused of witchcraft – doesn’t initially seem super relevant. What actually links the three is the enduring theme of male violence and how it impacts women.

I could easily have done without two of the storylines. I get what Wyld was trying to do, but I would personally have enjoyed it more if it followed only one story. Preferably the one about Ruth, who has recently married a cruel and unfaithful widower and is the unhappy mistress of a large and cold house. The different stories make the novel a jumbled and confusing mess at times with seemingly little connection between the three, except thematically. Further to this, the ending seemed, to me, nonsensical and a bit irritating.

Also, this is a bit of a minor point, but Viv – one of the narrators – describes making regular pilgrimages between her home down south and her grandmother’s house in North Berwick, which is in Scotland. This journey would take hours and hours and would require a number of comfort breaks. For some reason Evie Wyld writes it like it is a 10-minute drive to the shops.

Now, having said all that, I didn’t mind the book too much. I finished it, after all, and I did enjoy reading it. I just wouldn’t read it again, that’s all. 5/10.

Later on in May, the sun came out in earnest and I decided to read Banana Yoshimoto’s The Premonition, as translated by Asa Yoneda, which was nice and short. I read it over the course of an afternoon. I’ve read Yoshimoto before – Kitchen is one of my favourite books of all time – and The Premonition is a relatively recent addition to her works available in English, as it was translated in 2023 (the Japanese edition was published first in 1988).

Yayoi is a young woman who lives a nice, normal life with her nice, normal parents and nice, normal brother, but she also has a young, wayward aunt that she occasionally sneaks out to visit. But eventually Yayoi discovers a secret about her aunt – and herself - which alters the trajectory of her life. Yoshimoto’s works are comfortable and all-encompassing and I know I’ll enjoy anything as long as it’s written by her. The Premonition isn’t an exception. The characters feel very real and the book, whilst short, is complex, dealing with issues such as the bonds and bounds of family relationships and what it means to love. There is a familial relationship explored in the novel which goes to some very taboo places – this did set me ill at ease, to the extent that I actually don’t think a novel with themes like it could be written for a broad audience today. Enjoyed it nonetheless. 8/10.

After The Premonition I was in something of a slump. I hadn’t read a good fantasy novel for a while, so I picked up The House of Hunger by Alexis Henderson, which a friend had read and enjoyed. It is a rather different take on a vampire novel, which I appreciated (essentially, young women enter into service to wealthy lords and ladies, who – for a variety of weird reasons that are explained but which I do not really remember enough about – drink their blood for health and vitality). It’s quite gory and there’s also a fair bit of sex in it. Suffers from similar schlocky-ness that Maeve Fly did, though I do think the latter is written a bit better. I enjoyed reading The House of Hunger and pretty much devoured it (ha!) but there were bits and pieces that irritated me. For example, I was sat in the staff room at work reading it one day, when I happened upon the page with a brief and unremarked-upon revelation that the villainess’ name is essentially Elizabeth Bathory. I think I muttered ‘For fuck’s sake’ aloud. It loses points just for that, but I do have to still give it some for being relatively original and enjoyable to read. 5/10.

This next one is a bit weird. It’s called Mary and the Rabbit Dream by Noémi Kiss-Deáki and is about Mary Toft, a real-life eighteenth-century Englishwoman who was the centre of a great spectacle, a miracle, some sort of bizarre gift from God – she could birth rabbits.

Well, no, not really. Obviously Mary Toft could not birth rabbits, and obviously it was a hoax, and obviously she was punished for her indiscretion (sent to prison and charged as a ‘vile cheat and imposter’, later imprisoned for receiving stolen goods, and dying as poor as when she started). But for a brief time, a number of very educated, learned men – including the surgeon to the Royal Household – believed wholeheartedly that she could.

First, I’d heard of Mary Toft and had read her Wikipedia page. But for some reason it had never occurred to me exactly how she had convinced these men that she was birthing rabbits – or perhaps I simply didn’t want to know – but the various descriptions of her body being ‘open’ after a miscarriage and therefore open also to bits of, again, I cannot emphasise this enough, dead rabbits, had me gagging. Truly a foul and disgusting image, but I felt so sorry for poor Mary – who, in this narrative, is imagined to have committed such acts out of fear of the other, older women in her village – and sickened by the men who treated this medical curiosity as just a piece of meat, a specimen, rather than a human woman.

Another thing that Kiss-Deáki does, and to great effect, is her use of anaphora. Certain turns of phrase are repeated for dramatic and poetic effect, and to link sentences together. Turns of phrase which, when taken linked, give you the impression of sailing through the narrative. Sailing through the narrative on a boat made of rabbit parts.

Also, the book is beautifully presented. It’s published by Galley Beggar Press and they do this sometimes, and particularly here, where the text has thick white margins and line spacing you could sprint across. Coupled with the anaphora, this works wonders to make you feel like you’re reading super duper fast. 8/10.

The last book of April was Jacqueline Wilson’s Lola Rose. I read it when I was still part of Jackie’s target audience and remember liking it and thinking I was very grown-up for reading it, and having another look at it was motivated purely by nostalgia.

It being a children’s book, I was able to blast through it in about a day, but holy shit. It is about domestic violence, and then fleeing from that domestic violence, through the eyes of a child. I remembered parts of the book, and even particular lines, from my childhood, but as a child I didn’t have the capacity to be as horrified by it as I was now, re-reading it as an adult. The ending is very sad too; I seemed to think it ended on something of a hopeful note when I read it at age ten, but reading it now, it’s just misery all the way down. I think it can be a useful experience to read books one loved as a child with the new, experienced eyes of an adult, especially if those books are by authors like Wilson, who craft these stories about people in very desperate situations. As a child you see it one way; but seeing the decisions made and the fallout as an adult is different and enlightening. 5/10.

June

Three books in June. Spoiler alert – two absolute crackers and one that I did not understand and will definitely need to read again to really parse.

Paradise Logic by Sophie Kemp is about Reality Kahn, who lives in New York, works as an occasional actress in water park commercials, and decides that she is going to find a boyfriend. Sounds pretty standard but no – you wait. This book is one of the craziest and most bizarre I have ever read.

Smiley faces are used as punctuation. The narration is a nutty stream-of-consciousness which only gets more insane when Reality enters into a drug trial to become the perfect girlfriend for her shitty woke-misogynist boyfriend. The last word of the book is YOLO.

But my God, is it fun! It is SO FUN and I laughed out loud at various points. Beneath the veneer of general insanity, Kemp writes – with Reality as her conduit – with surprising clarity about topics such as sexism, modern dating, violations, consent and the lack thereof. Various parts of the book do not make sense and I saw Reality, really, as the logical endpoint of the Internet manic pixie cool-girl who seems to be becoming a staple of modern women’s literary fiction (I’ll discuss this more later on when I talk about Honor Levy’s My First Book; see also Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation for a Y2K version). This book was kooky and absurdist and downright mental and I, like Reality going down and down a waterslide, over and over again, loved it. 10/10.

So if Reality Kahn is floating off the planet, all astral weirdness and practically alien in her oddness, then Ruth’s feet are so deep in the mud that she’s stuck there, utterly transfixed down to Earth. Ruth – or Baby – is the protagonist of Brittany Newell’s Soft Core, which was the second book I read in June. Ruth is a stripper who seems, genuinely, to like her job (though I did not love the descriptions of her Pleasers and how they contort her feet – my toes crinkle at the thought). But Ruth has a problem – she is alone. Her drug-dealing boyfriend Dino has disappeared into thin air.

Through a series of events, she ends up working as a dominatrix, during which time she also ends up corresponding with a mysterious customer known as ‘Nobody’, who seems only to want to share his nihilistic, self-hating, suicidal thoughts with her over email. The San Francisco that Newell paints is dreamy and psychedelic and baked with heat. Tenderness bleeds into every word and each character, no matter how minute their role, is treated with a certain care and even respect, something so rarely afforded to those who work in such industries. Even Emeline, a younger stripper who is probably the closest thing Soft Core has to an antagonist, is written gently and caressed softly by Newell into being.

There is a part in this book, perhaps a third in, where Ruth is recounting the events of the first time she met Dino, and how quickly she fell in love with him. The imagery used here, the description, the feeling, all of it made my heart swell. I don’t necessarily remember exactly what was written, but I remember the feeling of reading it, and I remember thinking that it was one of the purest and most gorgeous descriptions of the feeling of falling for someone that I’ve read for a long time. 10/10.

June was going so well. The sun was out and hot and I wore sunglasses all the time. I went across to the bookshop to pick up a copy of Ed Atkins’ Old Food, which looked to be blessedly short and was published by Fitzcarraldo.

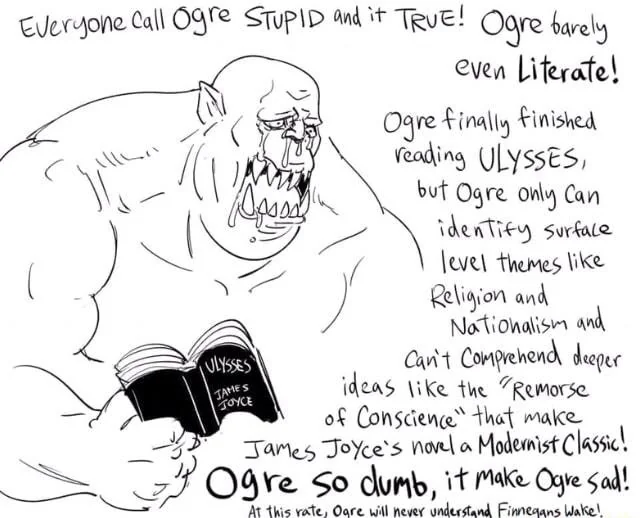

Well, to be perfectly candid, I didn’t dislike this one so much as I didn’t understand it. The experience of reading made me pissed off because I felt, continuously and increasingly, like this meme:

I really appreciate the depths of language that Atkins plumbs. He writes stylishly and cleanly and I can tell that he is talented, and I want to be clear that I do not think Old Food is a bad novel. I just don’t see why it had to be a novel. It apparently began as some sort of spoken-word art installation which would, I think, work much better.

I can’t even explain what it is about. I couldn’t follow it enough. Ogre barely even literate. I’m having a flick through it now whilst I type this and the mind reels. What is the plot of this? However, the writing is brilliant and the descriptions are sumptuous and this book made me damn hungry.

Also, like Galley Beggar Press, Fitzcarraldo do this lovely thing where the print is nice and big and the margins are huge. Probably necessary for this title, as it’s 130 pages with the non-standard typesetting and would, I imagine, barely scrape seventy without it.

Objectively, this is a very fine work. I can’t really explain why it is – like I said, ogre barely even literate – but I just know that it is. Atkins is a talented man.

Subjectively, I did not care for it. I’m sorry, Old Food. You deserve someone more literate than me. No rating.

July

Rang in July with a non-fiction pick, my second of the year. I have, for a little while, been pretty fixated on the Romanovs – particularly the most recent generation who, in 1917, were famously toppled and eventually murdered by the Bolsheviks, an event which helped usher in the formation of the USSR and greatly changed the trajectory of the modern world. So I read the esteemed historian Robert K. Massie’s Nicholas and Alexandra, which is a fascinating account of Tsar Nicholas II and Alexandra Feodorovna (formerly Princess Alix of Hesse and by Rhine, a granddaughter of Queen Victoria). Their reign was disastrous for a number of reasons but the most well-known one was the Tsarina’s trust and faith in the wandering starets, Grigori Rasputin.

Honestly, the reign of Nicholas, the lives of his family, and the way things all crumbled not all at once but slowly has all the markings of a fictional epic. I just really feel like if you, as a writer, wrote a novel that contained (for example) a sickly young prince who is almost dead but is miraculously healed by a sex-crazed ‘priest’ that your mother trusts and adores much to the horror of her sisters-in-law and this healing is instigated via telegram (‘Do not let the doctors bother him too much’), your editor would roll his eyes and tell you to take it out.

Obviously, this one is pretty niche because the lives of the late-stage Romanovs are a particular interest of mine. Also, it is worth pointing out that Nicholas and Alexandra was written in 1967. The Soviet government was very secretive about the murder of the Romanovs for quite some time, and so the book does end pretty abruptly. We know now that most of the bodies, having been dumped into a mine shaft and doused with sulphuric acid, were rediscovered in 1979 (though the discovery was kept under wraps until the USSR collapsed), and the final two bodies – those of the aforementioned sickly prince and one of the princesses – were discovered in 2007. Obviously it’s all quite grim, but it’s a fascinating period of history and Massie’s book in particular is very in-depth and humanising. 8/10.

After Nicholas and Alexandra I read Olga Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead, which I did attempt to read a couple of years ago, albeit unsuccessfully; I’d had lots of books to read and it was a library copy, and there were a lot of holds on it so I had to take it back prematurely. This time I dedicated myself to reading at least a little each day, as there were still lots of holds and I didn’t want a repeat of last time.

I’ve read Tokarczuk’s Flights and have had her incredibly intimidating magnum opus The Books of Jacob on my to-be-read list for quite some time. Drive Your Plow… is one of her shorter works and is a good starting point for anybody wanting to read Tokarczuk, and focuses on Janina Duszejko, an eccentric former teacher who looks after her neighbours’ homes when they aren’t there and helps a former student of hers, Dizzy, translate the poetry of William Blake. But within the opening pages, a local man is found dead, having choked on a bone.

And then later, a police officer is found dead too, followed by a local pimp, and then a priest; throughout all of these Janina is there, watching and commenting. These people all have one thing in common – but I won’t say what it is. Actually, Drive Your Plow… is hard to comment on without spoiling the ending, and even discussing some of the book’s themes and style is difficult; I greatly enjoyed it though and I would recommend. This was the book I chose to read to represent Poland for my Book World Tour and I am going to have another go-over of it at some point next year, so that I can do a proper write-up of it. For now, though, 8/10.

The next one was an anthology of short stories – the first and only one of the year – Honor Levy’s 2024 debut My First Book.

This one is nice and slim and – by virtue of being an anthology – is easy to read and parse and ease into. This possibly says more about me as a person than about the book, because the best-known thing about Levy’s book is just how chronically online it is. Some of the stories even contain URLs and passwords you can use to access web pages which contain, basically, explanations of memes referenced. Earlier I mentioned this idea of manic pixie Internet-oriented female protagonists, and though the stories in My First Book are mostly unlinked, there is a constant thread of seething girls raised on a steady diet of online misogyny, steeped in world-wide-web poison. Honor Levy is one of them, and – a quick Internet search confirms this – because we are roughly the same age, and because of how deeply My First Book spoke to me, so am I. Though I already knew that. If this applies to you too, give it a try. It will either enthral or infuriate you. And if you are not a twenty-something woman who had a desktop PC at way too young an age, you should still read it because it’s thoroughly decent, but you may find yourself a little more baffled than I was.

(Side note: My First Book pairs nicely with Prasifka’s This is How You Remember It. Prasifka’s book is a cautionary tale; this one is a glorious wild shriek from the other side, spoken by women well past the boundary). 8/10.

Next, I read – just like everybody else did this year – I Who Have Never Known Men by Jacqueline Harpman. Also known by its unfortunate original English title, Mistress of Silence, it was published first in French in 1995 and had an English-language release two years later. It was read and remarked upon and then gradually fell out of print, and from there of relevance.

Then for some reason, it got huge on TikTok.

Anyway, everybody read this book this year. I like to think that I’m not one to follow trends, but I did think I’d like to know quite what the hype was about. It was a book club pick but – as seems to be the case with lots of these mega-popular books – the library had under ten copies and a queue as long as my arm, so I had to buy it.

God, how bleak. How depressing. How weirdly compelling. Everybody and his mother has already commented on the empty misery that permeates every paragraph of this book, just as they have all compared it favourably to Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. A girl and thirty-nine women live in a cage underground, guarded by men, who do not speak to them; the women and girl aren’t really supposed to talk to each other, though they are occasionally able to. One day, an alarm sounds and the women and girl are able to escape, into a blank, empty world in which there is nothing else. Trees and plants, sure, but no other life. No birds, no animals, and – crucially – no other humans.

More than anything, this book is isolating. I read it during a pretty miserable time in my life, and because reading is a solitary hobby anyway, being by myself – in the staff room at work, on the couch of an evening, on the bus or the train – just amplified the misery. I think it signifies something dark about our society that people are engaging with this now, after the enforced isolation of the first part of this decade; it seems to speak to a deep isolation within a lot of people, something which is quite sad.

Damn. We really do live in a society.

Anyway, I realise that I’m not really selling it – the bleakness really can’t be overstated – but yes, it is very good. I enjoyed it, and what I love most about it is seeing new life breathed into a book that was formerly out of print and forgotten (a similar thing happened to Kay Dick’s They, which was rediscovered by a literary agent in a charity shop almost twenty years after Dick had died and was reprinted). Most books don’t get printed again after their initial run. It’s nice to see that there’s still some hope for the industry, and for the excellent creatives who keep it propped up. 8/10.

August

Well, I clearly had a stellar summer, because I only read one book this month. Making a return to the year’s first author, I read another of C.J. Leede’s, this one being her most recent novel, American Rapture. Sophie is a meek teenager from a strict Catholic background, with a disappeared brother and a desire to just get through the rest of her adolescence as best she can. Her life – and the lives of everyone around her – is upended when a pandemic begins to spread. Flu-like symptoms, rash-reddened palms, and an insatiable lust. Sounds fun to me.

I haven’t read a good apocalypse novel in a while and this one scratched a nice itch. It felt at times vaguely parodic, holding its subject matter at just enough of an arms’ length so as not to take itself too seriously. Sophie joins up with a band of survivors to try and make her way across the country so that she can reunite with her brother, who had previously been sent by his parents to a restrictive Christian school due to committing some vague and heinous crime (the details of which gradually become clear – but spoiler alert, this ‘crime’ would only be considered such to the most religious among us).

I found American Rapture to be an improvement on Leede’s earlier novel, Maeve Fly. The voices of both narrators were, I found, disconcertingly similar at times, which is disturbing as Maeve and Sophie are wildly different characters. It was easy to read (I breezed through it) and pretty gripping at points, though it suffered many of the same issues that other post-apocalyptic works have, like character bloat. I also feel like it could have been a bit shorter. But on the whole I did like it, and I would recommend. Having read two of hers now, I do actually think that C.J. Leede is one of the better and more original horror writers working today, so I probably will read her next novel when it comes out. 7/10.

September

My birthday is in September and I spent most of that day reading the month’s first book, V.E. Schwab’s Bury Our Bones in the Midnight Soil. A friend read it and, whilst reading it, said that she thought I’d like it; it was also wildly popular at the library so I did have to wait a little while. Disconcertingly, when the book arrived, my friend made sure to tell me that ‘it wasn’t the greatest book in the world or anything’. Hmm.

Bury Our Bones...is a vampire novel. I love a good vampire and I love them more when they’re of the lesbian variety, which this is. I have read one of V.E. Schwab’s before, Vicious, which I don’t remember much about beyond thinking that it was good fun. I had relatively positive expectations. I needn’t have bothered.

This was the longest novel I read this year (Massie’s Nicholas and Alexandra from July is slightly longer, but is a non-fiction work) and is also the one I am angriest about. Bury Our Bones… is about three women and is split over three different time periods, though the women at the centre of each story do eventually meet and their storylines converge. Maria is a spirited and determined young woman living in 16thcentury Spain, who is married to a cold and cruel count as a teenager. Charlotte is a sweet and quiet 18th century girl, awaiting her debut into society, having been sent away from home for the crime of having fallen in love with another girl. And in the 21st century we have Alice, who has moved from Scotland to the United States to go to university. All of them – spoiler alert! – become vampires.

V.E. Schwab was clearly trying to make some point about vampirism, about the eternal and sateless hunger that it causes, and also tries to further tie it up with themes of not belonging, of not being “normal”, and of being a lesbian (she is not the first to do this – a lot of vampire media has very homoerotic themes). She tries to do all of this in almost six hundred pages.

The biggest issue I had with this is its length. THIS BOOK DID NOT NEED TO BE AS LONG AS IT WAS. The story could have been told in perhaps four-hundred pages, and further to this, I really do not think we needed all three storylines. Maria’s story is fantastic and is clearly the ‘main’ one – I would probably have liked this book so much more if it focused exclusively on her. She spends a very long time living and meets a whole host of fascinating vampire characters in different places around the world, and these parts of the book were my favourites. I didn’t mind Charlotte’s plot – I do like Regency England as a historical setting – but it felt very thin and flat compared to the lush characterisation and deep emotion of Maria’s. Alice’s was utterly pointless and, dare I say, a bit dumb. You mean to tell me that this secret cabal of vampires, who have existed for hundreds of years, entrenched in mystery, are now kept track of by one of their number who runs a special coffee shop for other people with supernatural powers (other supernatural people, by the way, are not mentioned in any of the other storylines, except for the token cool girl who can read other people’s minds)? The pacing is also utterly diabolical. And the ending – THE ENDING – infuriated me. I’m going to spoil it because I don’t recommend anyone to waste their time with this, so – Maria, now called Sabine, is the cause of all the conflict up to this point and is known as an incredibly powerful and fearsome vampire. Alice, a new vampire, rocks up and just – kills her. In the shower. Turns her into dust. And that’s it.

The fuck?

In terms of writing, Schwab writes nicely enough, but the book did feel quite juvenile at points, and I did have to check that what I was reading was designed for adults rather than teenagers. Quite a few of the characters lack nuance or depth. By the time I got 300 pages in, I had checked out, but I didn’t want to let it beat me, so I had to finish it.

Don’t waste your time. The House of Hunger is a better vampire novel, as is Marina Yuszczuk’s Thirst which I read last year. 2/10.

Pissed off by how much time I’d wasted with Schwab’s abortive vampire effort, I wanted something slim and easy for my next read and so I settled on Saou Ichikawa’s Hunchback, translated by Polly Barton, which is under a hundred pages long. I breezed through it over the course of a morning. Hunchback is notable because the author is the first recipient of Japan’s prestigious Akutagawa Prize to have a disability.

Hunchback is about disability. It’s no secret that disabled people are treated pretty awfully in many societies around the world, with responses ranging from misplaced sympathy to outright derision, and Ichikawa – who has congenital myopathy – presumably knows this well. Her protagonist, Shaka, also has a disability (myotubular myopathy) and lives in a group home (which she actually owns, having come from a well-moneyed family). But Ichikawa, though undoubtedly drawing from her own experience, is careful not to turn Hunchback into the standard autobiographical first novel. Shaka is introspective and learned, earning money by writing pornography. Her literary works open the novel and, seemingly, close it out too; her works are representative of her own desires, something which is transgressive in a society that seeks to de-sexualise disabled people as far as possible. One of the carers at Shaka’s house, a young man named Tanaka, discovers her career, and a deal is struck – Tanaka, who could use the money, will be paid by Shaka to have sex with her. This would pose a major safeguarding concern in real life, and as Ichikawa discusses, there is a power imbalance between the two, although not necessarily in the way you’d think. Tanaka is on a low wage, whilst Shaka not only has serious money (she doesn’t even keep her earnings from her writing, instead donating them to charity), it is her home that pays his wages. He wouldn’t even have a job if not for her, so the offer of money to have sex with someone is clearly quite tempting.

Shaka ruminates, throughout the course of the novel, on the ableism of reading and bookshops (and not even just those with floors to narrow for a wheelchair to course through; “[…]being able to see; being able to hold a book; being able to turn its pages; being able to maintain a reading posture; being able to go to a bookshop to buy a book—I loathed the exclusionary machismo of book culture that demanded that its participants meet these five criteria of able-bodiedness”.) She also discusses the films of David Lynch, the infamous vandalism of the Mona Lisa by disabled women’s rights activist Tomoko Yonezu, and of course, sex.

The book’s receipt of the Akutagawa Prize is well-deserved. I really enjoyed reading this, and I also want to mention Polly Barton’s translation; I’ve read a few of hers before (notably her translation of Asako Yuzuki’s Butter), and I really think she is a great translator. Japanese is notoriously difficult to translate, so I really appreciated the effort that Barton went to with Hunchback. 8/10.

The final book of September was A Ghost in the Throat, by Doireann Ní Ghríofa, which is (technically) non-fiction, though I think it definitely has autofiction elements.

I read a few translated books this year, as I do usually, and A Ghost in the Throat might be the best example of one. Strangely enough, I actually can’t determine which language the book was originally written in – Ní Ghríofa is an Irish poet who writes in both Irish and English – but the focus of the book is an eighteenth-century Irish poem (caoineadh, or keen) written by a noblewoman, Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill after the death of her husband.

A Ghost in the Throat is a female text. So states Ní Ghríofa at the book’s opening, and we see that reflected throughout – Ní Ghríofa tells us about her shopping lists, her endless cleaning, the dropping off and picking up of the children from school. These are not, to be fair, exclusively female things – but some of the other things she does (giving birth prematurely and traumatically, endlessly pumping breast milk for donation, a thick and desperate desire for another baby) are. This femaleness (not femininity, very much not) permeates the whole text, from Ní Ghríofa’s twenty-first century life to that of the poet and noblewoman Eibhlín Dubh.

Eibhlín Dubh is married off at fifteen, and made a young widow mere months later. A few years after this, she falls in love with and marries the swaggering army captain Art Ó Laoghaire, with whom she has three children. Art is shot on the order of a magistrate with whom he has a long-running feud, and Eibhlín Dubh, frantic, falls to his dying body. She cups mouthfuls of his blood, drinks them so that he may always remain with her. In her grief, she composes the caoineadh, Caoineadh Airt Uí Laoghaire (translated and Anglicised to ‘Lament for Art O’Leary’). The caoineadh is the basis of A Ghost in the Throat, which is a lyrical and masterful exploration of femaleness, history, and how these two things intertwine; chiefly, how women’s voices, bodies, and experiences are erased from records.

Nothing demonstrates this more clearly than the author’s years-long hunt for the history behind the poem, stemming from an adolescent obsession (according to an Irish acquaintance, Caoineadh Airt Uí Laoghaire was widely taught at secondary schools until quite recently); at multiple points, she reaches dead ends, because although Eibhlín Dubh’s early life, marriages, and children are known, the facts of her life after her husband’s death are not. I won’t exactly spoil the ending, such that there is, but I would recommend you to read it for yourself. In many respects, A Ghost in the Throat is a love story – the love between Eibhlín Dubh and Art, between the writer Doireann Ní Ghríofa and her husband, and between Ní Ghríofa, and Eibhlín Dubh, and the poem – all of these twist and swirl and meet in one great beautiful work that is as much a poem as the caoineadh itself. Easy 10/10; the easiest on this list, probably the easiest I have ever given.

October

By October it began to get really quite cold, and as the dark and creepy nights began to draw in, I think I spent more time playing Disco Elysium than reading as the only book I finished this month was Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead, published in 2004.

Gilead is the first of Robinson’s that I’ve read. Reverend John Ames is seventy-six, and dying. With his much younger wife, he has one son, who is seven years old. Ames knows that his son will not remember him and so, wanting to leave him something, he writes him letters. The letters make up the content of Gilead, which is as much about religion and the nature of God as about Ames’ own life and family history.

I am not religious, nor was I raised to be; I also lack knowledge of Calvinism, which is the particular denomination to which Ames and his family belong. As a result, I think I am missing some of the required context to understand some of the discussions had in Gilead, which is why I think it will be deserving of a revisit in future. Despite not being religious, I always appreciate religion and the musing on such when it comes from somebody who is. And they have to actually be, not someone who is pretending; they have to be completely and truly invested in it, their whole essence imbued with their God, or Gods, or whatever else. Ames is, and I can tell just by reading every word Robinson writes that she is, too.

Gilead is quiet and calm, a small country house in a small country community. Every word is soft and the conflict, deep though it is, is tempered constantly with soft remarks, forgiveness and, at the end, a blessing. It is as much as treatise on the nature of faith as it is a novel, and there are passages which took my breath away; Robinson’s writing is delicate, never overwrought, and sensitive. Deserving of the Pulitzer and also of your time. 8/10.

November

In November I read only two, but one of them was by Thomas Pynchon so it basically felt like ten novels, a textbook and a history lesson all rolled into one (I’ll get there).

First up was Maddie Mortimer’s experimental 2022 debut, Maps of Our Spectacular Bodies. Where to even begin?

Lia, a children’s book illustrator, has beaten cancer once before. But now it is back, and it has a voice. Interspersed with third-person narration following Lia, her daughter Iris, her husband Harry, we hear from the ‘I’, the destroyer, the cancer ravaging Lia’s body. At points, these sections are hard to read, both physically and emotionally; text is distorted, by turns large and small, a disjointed nightmare on the page. Lia grapples with her past, her religious parents, her relationship with her daughter, all whilst ‘I’ kills her slowly from within.

This one is hard to discuss without spoiling, so I will have to keep it relatively brief. I have never read a novel with such astonishing power, where language is so carefully and painfully employed to illustrate what is going on; at times it should be hard to distinguish who is speaking, but Mortimer does such a stellar job at dividing up this linguistic power that it becomes clear who is who. Another point that warrants mention is the pain, both physical and mental, that leaks through each page. Not only are the characters imbued with it, but agony pours from the text, welling up from one source, the writer. Mortimer’s mother died of cancer when she was a teenager. This tragedy is clearly the place from which Maps...is born, in which it suffers. But the book shines, it excels, from this deep well of pain.

The book isn’t without its issues – it’s a tad too long, and some of the metaphors are rather overwrought – but this is Mortimer’s first book, published whilst she was in her early twenties. This book, the ending of this book, made me sob on a crowded train whilst everybody looked at me like I was mental. It made me feel. It will make you feel too. 9/10.

I was so emotionally destroyed by Maps...that I had to take some room to breathe before I started work on the next one, but to be fair there’s no amount of time that would have prepared me for it. Shadow Ticket is Thomas Pynchon’s most recent (and probably last) novel and oh boy, is it a doozy.

So I’ll start by echoing my earlier sentiment of being a barely literate ogre, and I’d also like to point out that I’ve read Pynchon before (

So, Hicks McTaggart is a down-on-his-luck private investigator in 1933 Milwaukee, who – after a bizarre series of events, culminating in his attempted murder via bomb delivered by two Christmas elves – ends up hightailing it across the sea to Hungary to track down Daphne Airmont, the heiress to a cheez [sic] company, whose father is the “Al Capone of Cheez [sic, again]”.

Yeah. It’s that kind of book.

But then all of Pynchon’s are, aren’t they? He has the reputation he does for a reason. Shadow Ticket is dense and complex, and I think it took me double the time it would take a normal person to read it because I had to keep going back to the previous few pages to ensure that what was said had actually sunk in. It’s satirical, make no mistake; but many of the themes it explores, such as the rise of fascism (Pynchon does a stellar job of comparing the current world situation to the rise of the Nazis in 1930s Germany), are not. There are too many characters and too little of a focus on the supernatural elements – I would have liked to have seen more discussion on just what the hell ‘apporting’ is supposed to be – but then if there was such a thing as an explanation then it wouldn’t really be in the spirit of the thing, would it? The prose is razor-sharp and tickles an itch in my brain that I didn’t know was there, and the novel itself was so paranoic that I found myself looking over my shoulder at points. Will maybe get a revisit if I can carve out a clean month with literally nothing else in my diary. I would like as much as the next person to get this understood. 8.5/10.

December

And then there were two.

The first read of December was People Like Her by Ellery Lloyd. I wanted something simple to read after the headfuck that was Shadow Ticket, so I thought a thriller that I grabbed from the library shelf with only a cursory glance at the blurb would do.

Emmy is a hugely successful influencer, who has earned millions of followers and substantial money by showing her children and family under the online moniker Mamabare. Though she tries to be relatable to her followers, Emmy’s previous career in fashion marketing made her a prime candidate for influencer stardom. Her meteoric rise was carefully planned, though she goes to great pains to ensure that nobody finds out. Her husband, Dan, is a mostly unsuccessful novelist who is furious with envy at his wife’s success. However, something is going wrong for the family. Somebody is following them, trying to catch Emmy out. Her marriage is beginning to crumble. Interspersed between chapters narrated alternately by Emmy and Dan are mysterious passages by somebody who seems to know Emmy, and is hellbent on destroying her life.

It was overwhelmingly okay. I don’t usually read thrillers because they are, to me, rarely thrilling. This one did grip me inasmuch as I wanted to see what sort of terrible fate befell the characters. Emmy and Dan are very hate-able and are deliberately written to be so; Emmy is a liar who constructs everything around a false narrative, and Dan is self-obsessed. They also seem to really dislike each other despite being married. People Like Her absolutely beats you over the head with its message that putting your children online and making a career out of them is bad, guys. The prose is also rather simplistic, but this does make it pretty easy to get into.

One high point is that the book is actually pretty funny. I mean, it’s not the most hilarious thing I’ve ever read, but as mass-market thrillers go, it made me chuckle more than I thought. I also enjoyed the parts revolving around the online gossip forums (Tattle.life is referred to by name, which made me smile; it’s breached containment, though Emmy’s thread doesn’t have a rhyming title so Lloyd loses research points there).

Unfortunately, the humour isn’t really enough to save it. The pacing is a bit off, probably because of the decision to split the narrative across three characters, one of whom we know nothing about until the very end. And speaking of the end – why? I actually didn’t hate the setup for it, and I think it would have been a better book if the authors (Ellery Lloyd is a pseudonym; it’s actually two people) had ended it before the epilogue. It would have stuck in my mind more, but (spoiler alert) I guess nobody wants a dead mum and baby. 6/10.

And now we approach the final book of the year – Jonathan Ames’ hardboiled detective thriller A Man Named Doll, published in 2021. The titular Happy “Hank” Doll (yes, really) is a charming ex-military private detective who moonlights as security at a *cough cough* “massage parlour”. Otherwise, he lives a quiet life with his little dog George and takes drugs and drinks to cope with his pretty nasty childhood, the exact course of which does become a bit clearer as the novel goes on. A former comrade of his, Lou, attends his office one day with desperation – he needs a kidney. Doll isn’t really in a position to give him one, but it doesn’t matter, because not long after this, he dies. But not before Doll accidentally kills a man who is trying to kill one of the girls at the massage parlour.

And from this point, Doll ends up ever so slightly out of his depth.

Ames (no relation, I am sure, to Gilead’s narrator) weaves a brilliantly compelling tale which is certainly steeped in good, old-fashioned Hollywood noir but stops just short of actually being it. Doll is too likeable and sardonic to be a convincing noir protagonist, a sort of proto-Hicks McTaggart, but I think this is because Ames was going for a slightly more parodic take than is traditional. (Also, minor point, but Doll spends a huge chunk of the book horrifically injured with no detail as to the weeping facial gash spared, and so Ames gets the award for making Merlo flinch every time she turns the page). The prose is tight and concise – no sentence is wasted, every word deliberate – and I found myself flying through it.

Great read. Easy 9/10.

And there we have it! All thirty-one of the books I read this year, laid out for anybody still reading. Here is to another year of reading, of learning, of enjoying life. Next year, I plan to read:

- Sarah Hall’s Helm

- Tao Lin’s Leave Society

- Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov (finally!)

- More non-fiction – I have an Andrea Dworkin (Right Wing Women) and a Joan Didion (Slouching Towards Bethlehem) sitting on my shelf

- The Trees by Percival Everett

- The Mind Reels by Frederik de Boer

- Anything published by Peirene Press, a small publisher that specialise in works in translation – I spent some time subscribed to them so now I have half a shelf of beautiful new paperbacks that I haven’t even cracked the spines of

- And many more!

If you made it this far, thank you for reading. I hope you have all read some good books this year, too.